The DAVINCI Mission

The DAVINCI (Deep Atmosphere Venus Investigation of Noble gases, Chemistry, and Imaging) mission will explore whether the inhospitable surface of Venus could once have been a twin of Earth – a habitable world with liquid water oceans.

Old Data Yields New Secrets as NASA’s DAVINCI Preps for Venus Trip

Due to launch in the early 2030s, NASA’s DAVINCI mission will investigate whether Venus — a sweltering world wrapped in an atmosphere of noxious gases — once had oceans and continents like Earth.

Consisting of a flyby spacecraft and descent probe, DAVINCI will focus on a mountainous region called Alpha Regio, a possible ancient continent. Though a handful of international spacecraft plunged through Venus’ atmosphere between 1970 and 1985, DAVINCI’s probe will be the first to capture images of this intriguing terrain ever taken from below Venus’ thick and opaque clouds.

But how does a team prepare for a mission to a planet that hasn’t seen an atmospheric probe in nearly 50 years, and that tends to crush or melt its spacecraft visitors?

Scientists leading the DAVINCI mission started by using modern data-analysis techniques to pore over decades-old data from previous Venus missions. Their goal is to arrive at our neighboring planet with as much detail as possible. This will allow scientists to most effectively use the probe’s descent time to collect new information that can help answer longstanding questions about Venus’ evolutionary path and why it diverged drastically from Earth’s.

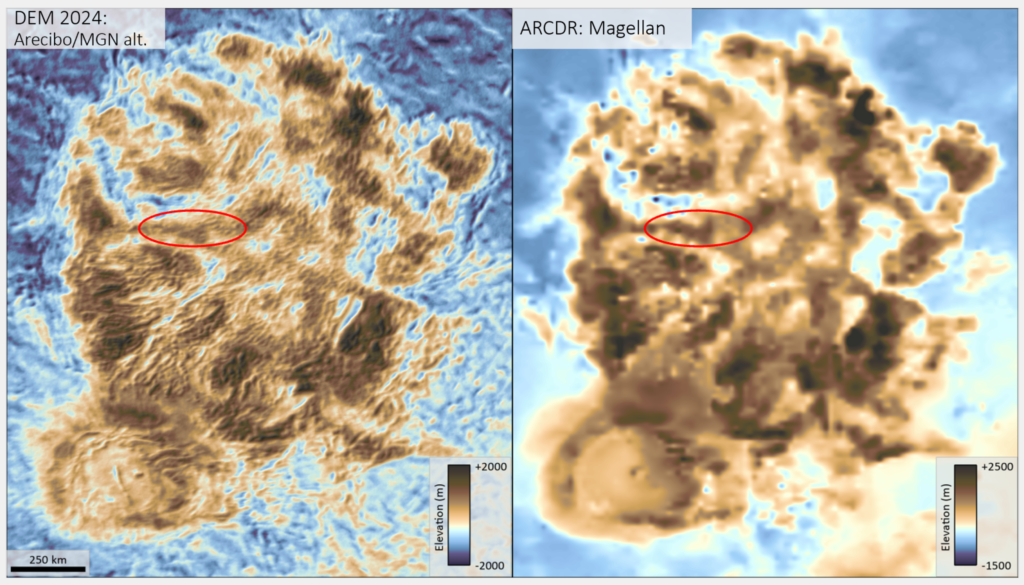

Between 1990 and 1994, NASA’s Magellan spacecraft used radar imaging and altimetry to map the topography of Alpha Regio from Venus’ orbit. Recently, NASA’s DAVINICI’s team sought more detail from these maps, so scientists applied new techniques to analyze Magellan’s radar altimeter data. They then supplemented this data with radar images taken on three occasions from the former Arecibo Observatory in Puerto Rico and used machine vision computer models to scrutinize the data and fill in gaps in information at new scales (less than 0.6 miles, or 1 kilometer).

As a result, scientists improved the resolution of Alpha Regio maps tenfold, predicting new geologic patterns on the surface and prompting questions about how these patterns could have formed in Alpha Regio’s mountains.